As a Section B reserve, Patrick received a retainer of 3 shillings and 6 pence (3s 6d) per week. This is roughly equivalent to £25 in today’s terms. He could only be called upon in the event of a general mobilisation. He was required to attend an annual training camp of three to four weeks.

It is possible that Patrick spent some time as a Section A Reserve. The pay was better (double the Section B figure) but he would have had to agree to be recalled in an emergency that fell short of General Mobilisation. At that time, trouble in Ireland would have been the most likely reason for a recall of Section A Reservists. As his roots were in Ireland, serving there in the event of unrest would have presented him with a moral dilemma. Given his indifferent disciplinary record, it is not clear whether the extra money would have swayed him. Time in Section A was limited to two years, so he would have transitioned to the lower level in 1912 at the latest.

As stated in “Boots were made for walking – part 2”, Patrick was only 2 months from the expiry of his time on Reserve when war was declared. I assume that most annual camps took place in the summer. Holiday entitlement was far less generous pre-WW1 than it is today. It would make sense to align training periods with factory summer shutdowns. If so, Patrick might well have been due to attend a camp only days before war was declared. There would have been a degree of ‘rustiness’ in his skill levels.

The timing of events is interesting. The Manchester Regiment was told to start preparing to mobilise on 4th August. It would be highly surprising if plans had not been made well before this date. The military likes to have plans to cover most eventualities. Mobilisation telegrams were sent out on that day. On 5th August, The Morning Post reported (on an inside page, as was the common at the time) that War had been declared at 7pm the previous day. This is ahead of the expiry of the ultimatum sent to Germany to withdraw its troops from Belgium. The Privy Council, at which King George V signed the official paperwork, did not meet until nearly midnight. The ‘At War’ mobilisation telegrams were sent out shortly afterwards.

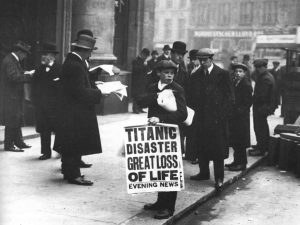

Once the decisions had been made, and then made official, the news had to be communicated to all parts of the country. No internet, no text messages, no emails, not even any commercial radio stations. There were over 750,000 telephones, but most of these were in businesses and the homes of the wealthy. Telegrams were used but the volume was limited by the capacity of the system: one message, one messenger. The main way to reach the bulk of the population was via the newspapers. At the time, there were over 600 daily newspapers. Other periodicals (weeklies etc.) pushed the total over 1000. The vendors could be relied upon to shout the main news items to attract trade. (The photo shows people learning about a major event in 1912.)  Once one person picked up the details, they would tell everyone around. It was, by the standards of the time, an efficient system. Notices were also posted in Town Halls. It would have been very difficult for someone to claim that they did not know what was happening.

Once one person picked up the details, they would tell everyone around. It was, by the standards of the time, an efficient system. Notices were also posted in Town Halls. It would have been very difficult for someone to claim that they did not know what was happening.

I do not know how Patrick picked up the news. He reported to the Manchester Regiment Depot in Ashton-under-Lyne on 5th August. As his journey started in Dewsbury, it is safe to assume that he arrived in the afternoon, possibly the evening.

The War Diary reports that contingents of Reserves arrived in Ireland (where the 2nd Battalion was serving at the time) on 7th and 8th August. The trip can now be made in less than half a day using commercial flights. In 1914, by land and sea, using public transport, those troops must have set off a day earlier. Perhaps there was simply not enough time to add Patrick’s name to the list of those scheduled to travel.

Whatever the reasons, he did not accompany the 1015 of his fellow soldiers of the 2nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment who set off on 13th August. (see ‘Would not start from here’)