In the blog ‘Medal Ribbons’ I briefly examined the question of how many soldiers survived the entire war in their original unit. Fate played a part. Being in the right, or wrong, place could make a massive difference to the chances of survival. Examination of three seminal battles helps to prove the point.

1914: In August 1914, the 2nd Battalion of the Manchester Regiment was in Ireland. They were thrown into battle within days, and suffered big losses (see ‘These boots were made for walking – Part 1’). Their colleagues in the 1st Battalion were in India when war was declared. They hurriedly packed up and set forth, by train, boat and then more trains. They did not arrive on the Western Front until late October. Their first fatality was incurred on 27th October. By this time, the 2nd battalion had lost well over 200 men.

1916: The First Day of the Battle of the Somme saw the worst casualties that the British Army had ever incurred. Some of the battalions leading the first wave of the advance were almost wiped out. The Accrington Pals (more correctly, the 11th Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment) had one third killed (235) and half wounded (350) within the first thirty minutes. Many are buried in the Queens Cemetery (pictured)  The 2nd Battalion, Manchester Regiment, had a support role on that day. They were supposed to push on through the first wave, to consolidate the gains made, and then continue the advance. Things did not go to plan. Despite not being in the first wave, the 2nd battalion still lost 11 killed that day and 21 the following day. Serious losses, but small by comparison to other units. (The 1st Battalion, Manchester Regiment had been transferred to the Middle East by this time. Patrick was back in England.)

The 2nd Battalion, Manchester Regiment, had a support role on that day. They were supposed to push on through the first wave, to consolidate the gains made, and then continue the advance. Things did not go to plan. Despite not being in the first wave, the 2nd battalion still lost 11 killed that day and 21 the following day. Serious losses, but small by comparison to other units. (The 1st Battalion, Manchester Regiment had been transferred to the Middle East by this time. Patrick was back in England.)

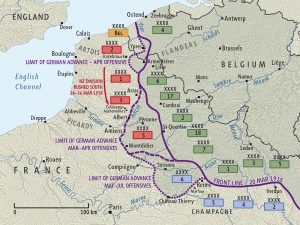

1918: On 21st March, the Germans launched their Spring Offensive. The attack was expected, but there were many options for the location. The initial assault took place over much of the same ground as the 1916 Battle of the Somme. The target was the key railway town of Amiens. Units in that area were subject to an intensive artillery barrage, followed by an attack by large numbers of highly trained troops. The momentum of the offensive was such that Allied troops were forced to fall back. A fighting retreat is always likely to incur serious casualties. This was the case in March 1918. At the time, the 2nd Battalion was defending a stretch of the line near Langemark, north of Ypres, about 80 miles away. They had not moved significantly since the award of medal ribbons at the beginning of February. The War Diary records that enemy artillery was unusually active, firing a mixture of High Explosive and Gas shells. Six men were wounded.

The 10th Battalion of the Essex Regiment were amongst those that took the full force of the attack. They lost 37 men on the first day, 78 in five days, and 135 in four weeks. Many others were wounded and captured. It could so easily have been the Manchester Regiment incurring this level of casualties. (Their figures for the same periods were 0, 2 and 15 respectively.)

The 10th Battalion of the Essex Regiment were amongst those that took the full force of the attack. They lost 37 men on the first day, 78 in five days, and 135 in four weeks. Many others were wounded and captured. It could so easily have been the Manchester Regiment incurring this level of casualties. (Their figures for the same periods were 0, 2 and 15 respectively.)

At the end of March 1918, the 2nd Battalion was moved south. They took up positions near Arras. They were on the extreme end of the bulge that had been created in the line by the Spring Offensive. It wasn’t exactly a quiet posting, but it was a lot quieter than many other places. For good or bad, fate played a large part in determining the odds of survival.